I’ve always considered myself an accepting person. Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, I always knew when certain things felt right or wrong, when it was important to push for progress.

But all of that always pointed outward. As a Chinese-American and a child of immigrants, internal acceptance came much harder; in fact, on the cusp of 40, it’s still a struggle. No matter how much I fought for others, it was difficult to fight for myself — even in the face of explicit racism towards my parents. In those situations, a lot of internalized victim-blaming happened. “If only my parents weren’t so Chinese” or “if only they weren’t so frugal” or “if only their accents weren’t so thick.”

Because I hated being Chinese. The constant messages from culture were obvious: Asians of any type weren’t cool or sexy or heroic. And even if Asians made it on screen, we were all lumped together into one generic Asian bucket, regardless of South Asian, South-East Asian, West Asian and Central Asian identities.

If I wanted to avoid being picked on, if I wanted to be seen as cool, if I wanted to ever get a girlfriend, then I needed to avoid my ethnicity.

Ironically, this self-loathing was a driving component that turned me into who I am today.

I pushed myself to not be my ethnicity, and for a lot of my childhood, this meant being things that weren’t fitting into that stereotype. Chinese were quiet and reserved, so I wanted to do theater and write. Chinese trained in piano and violin, so while I took piano lessons for since age 4, I picked up the guitar as soon as I could and started playing in bands, even DJing. Chinese didn’t push the boundaries, so I gravitated to things Chinese didn’t typically like: punk rock, hockey, the arts.

And writing.

But my writing is where this self-erasure of my ethnicity rose to the surface. And realizing what had happened — and why — took a little help from some new friends.

See, I was so used to seeing heroes who didn’t look like me that I would default to white when creating characters. And when I considered making them Asian, all sorts of feelings stirred around that. I feared being accused of self-projection, of putting the focus on myself rather than the story. I actively avoided to not have Asians, particularly East-Asians, in my books.

My debut novel HERE AND NOW AND THEN. It’s got a diverse cast, starting with the hero who looks like Idris Elba. I’ve talked about trying to represent the world I want to see with this future (a good chunk of the book takes place in 2142), and there’s even a line in there about how family names no longer represent ethnicity because, like my own daughter, so many multiracial children have been born over generations after 2000 that it everything has melted together. When filling out this world, I made sure to follow this by spreading out and mixing up names of origin, skin color, and other such traits, turning the levers randomly up and down as if I was building RPG characters in a video game. It’s a spectrum, but one thing that I didn’t do was have a clear East-Asian protagonist, not even in the supporting cast. They’re there, but in the background.

Looking back now, this seems like such an odd decision. Whenever I saw East-Asian heroes in media, it was always such a thrill — from introducing college dorm-mates to the awesomeness of Chow Yun-Fat in Hard Boiled to seeing Glenn Rhee on The Walking Dead become a fan favorite. I knew how seeing proper representation felt, and yet I couldn’t do it myself. In fact, I never considered it thanks to the biases built into me from birth.

This past August, I attended Worldcon 2018 in San Jose. It was my first convention as an author, and while my goal was to meet as many fellow authors as I could, a strange thing happened among all of the alcohol and caffeine and hand-shaking. During those conversations, particularly with a spectrum of other Asian authors, I understood for the first time the depth of my internalized shame — and why we as Asians have to work extra hard to create representation.

It’s a stereotype that’s true: for Chinese-Americans like myself, we are raised with this weird combination of internalized shame and unchecked selflessness. We are taught to always think about the family and never to think about ourselves, and the byproduct of this as creatives is that it can be hard to insert any version of yourself into your work.

(Yes, I know that this isn’t everyone. But every Chinese-American friend I know — heck, every Asian friend I know — has battled with exact set of demons to some degree. There’s a reason why there are studies on the topic.)

There was a strangely consistent throughline in many of my discussions with other Asian writers: a lot of them struggled to use leads that looked like themselves in their first few novels. At the same time, Jon Chu’s film adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians was about to come out, and there was also a lot of discussion about how it was such a relief to see people like myself on screen being sexy, romantic, even superficial assholes — anything outside of the smart/geeky/quiet stereotype that is still pervasive.

The discussion about self-projection, internalized shame, fact that other Asian creatives struggled with that, all of that created quite the epiphany. That, combined with the talk about Crazy Rich Asians, crystalized a thought in me, not only blowing open the doors on a lifetime of self-loathing (hello, therapy), but also the importance of representation.

Because of our cultural and family biases, us Asians across the entire spectrum are pretty much terrible at self-promotion. We are constantly okay with passing the spotlight onto someone else, and because of that, it’s difficult to really stand up for ourselves and our identity — our culture has created a vicious cycle of self-erasure. How can something become visible if it’s predispositioned to remove itself and not complain about it? To break that, it will take a generation of creatives to show a diverse volume of Asian people. They can be heroes or villains, sexy or assholes, doctors or construction workers; their ethnicity can draw from being South Asian, South-East Asian, West Asian or Central Asian. The important thing is that they exist, they are there.

Because representation matters.

To that skinny Chinese kid who was called a Chink just for going to a 7-11 on vacation in Reno, seeing Glenn fight zombies or discovering that Crazy Rich Asians dominated the American box office might have changed everything. I can’t go back in time to tell my pre-teen self that (even though I am writing about time travel), but I can do better for the next generation and show Asians in my work.

To that end, I fought a lot of internal battles to make one of my book 2’s protagonists (there are three) half-Japanese. That book is currently in final revisions for an early 2020 release, and making that kind of commitment required a gradual shift in my own internal sense of self. It seems like something that, to the outside observer, should be an easy objective decision, but we’re talking about undoing decades of internalized bullshit. Today, I’m a little steadier, and as I look ahead to my current WIP manuscript, one of the two heroes is Chinese and I am finally comfortable with that.

Will I be accused of wish-fulfilment? Maybe, but it’s a different kind of wish. I’m not self-projecting myself as a hero of my own fantasies. I’m picturing a world where people who look like me exist, where they matter.

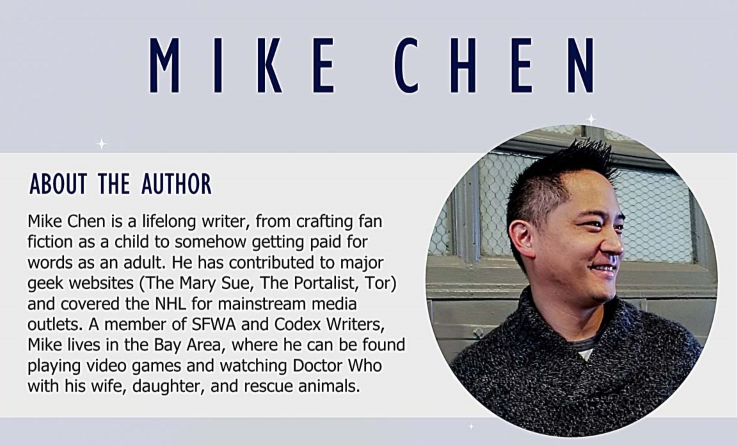

Thanks so much Mike! Readers can find Mike on his website, Twitter and Instagram. Lookout for his sci-fi book, Here and Now and Then, coming out on 29 January 2019!

[…] Lit Celebr-Asian: Defeating Self-Defeat in Asian Representation – A Guest Post by Mike Chen […]

LikeLike

[…] and Matt Kressel. Thank you all for telling me to "shut up and stop apologizing for everything." As a Very Asian Person, sometimes I need to hear […]

LikeLike